A unique bike that won 67 races in its development season

The current globalisation of road racing means that, in almost every country of the world, in every class, the same identikit array of Supersomethings line up on the grid to compete against each other for the chequered flag. The same Superbikes, the same Supersports, the same Superstocks, all with engines and chassis basically more or less just as they rolled off the assembly line in Hamamatsu or Bologna, Hinckley or Iwata. To make matters worse, Dorna and the FIM conspired to bin the 250GP class in favour of Formula Honda 600, where not so long there used ago to be lots of variety, with small manufacturers or specialist tuning houses producing their own complete bikes (think Parisienne, Armstrong, Pernod etc.) – or, more commonly, slotting a Yamaha or Rotax motor into their own unique chassis design. Look at the 250GP entry list of 30 years ago, and quite apart from a little company called Aprilia that started out in road racing wrapping its own frame around a Rotax engine, there were JJ-Cobas, Real, Spondon, Gazzaniga, Harris, WIWA, Roemer, Bakker, Chevallier, Ringhini etc. etc. – need I go on?

Which puts properly into perspective the achievement of the two partners in a small British company called Exactweld in winning the 1984 European 250cc Championship with its self-constructed, self-tuned and especially self-financed TZ Yamaha-engined racer – an ultra-light, voluptuously streamlined creation which had the honour of being the first 250GP motorcycle to break the 90kg class weight barrier – it had to carry lead to be allowed to race. On it, 22-year old Gary Noel won the Euro-title in time off from working as a British Airways diesel mechanic, scoring victory in the hotly contested 11-round series by a single point from French Yamaha importer Sonauto’s Philippe Pagano. The irony of a couple of blokes and their part-time rider working with a bunch of unpaid helpers out of the back of a Transit van to defeat a fully-sponsored team with paid mechanics and factory support, complete with artic transporter, a separate hospitality unit and paddock spares cache, is deliciously British – underdogs are GO!! But the fact that Exactweld partners Guy Pearson and John Baldwin achieved this feat owes much not only to their dedication and perseverance, as well as Gary Noel’s hard but clear-headed riding, but also to the innovative engineering incorporated in their self-built bike. See, little guys can win if they box clever – and the Exactweld 250 was a VERY clever bike.

Other hot stories: BMW R1200GS vs Honda CRF1000L Africa Twin: in-depth review

Building a record-breaking double Ducati for Bonneville

Based south of London at East Grinstead, West Sussex, Exactweld was founded in 1977 by Pearson and Baldwin, who’d met up while working at Team Surtees in nearby Edenbridge, fabricating aluminium monocoque chassis for John Surtees’ Formula 1 cars. The firm made orthopaedic tools for the surgical profession, as well as specialist fabrications for the food industry and vintage car world – in the Exactweld factory you could expect to find an engine block from a prewar Auto-Union GP car, or a postwar BRM Formula 1 cylinder head sharing workshop space with a North Sea oilfield vacuum pump or a 250GP bike chassis, waiting in line to benefit from the Exactweld duo’s welding skills. But most of the profits were poured back into the two partners’ passion for motorcycle racing, resulting in a total of 12 of the special Exactweld frames being constructed, all with Yamaha motors. The firm’s Sincrowave TIG welder then representing a five-figure investment in sterling terms was just the most expensive of Exactweld's several high-precision tools, all of which earned their keep in fields totally unrelated to bikes. “Nobody's got any money in the bike world," John Baldwin once told me, "so this is only a hobby, which means it just occupies most of our time, instead of all of it!" One which did eventually earn them some cash, though, when neighbouring entrepreneur Bob Graves hired Exactweld to create the remarkable Norton Cosworth-engined Quantel BoTT racer which defeated the new Ducati desmoquattro Superbikes to win the Daytona Twins race in 1988, to become the world’s top twin – for a while……

But before then, Exactweld had built its first 250GP racer in 1978, employing what would come to be its trademark format of a stainless steel spine frame housing a TZ250 Yamaha motor. The concept was gradually refined in British club racing in the hands of various riders, before stepping up a level in 1982 when Gary Noel began riding the bikes, powered by year-old Yamaha H-model engines tuned by the team. In just his third year of racing, Noel won both the 250cc and 350cc Racing 50 Club championships, as well as the Bemsee 250 crown on the Exactweld-framed Yamahas, a season of dominance he repeated in 1983, winning an amazing 69 races including a British National championship round at Snetterton. But both he and the Exactweld duo had already bucked the trend for UK riders to stay at home and make a comfy living riding week in, week out, in Britain, rather than seek to climb the international ladder – a custom still pertaining today. Hitting the ’83 European 250cc Championship trail resulted in seventh place at Chimay in Belgium, tenth at Assen, as well as sixth in the British round at Donington – good training for a serious tilt at the title in 1984, with an encouraging showing at the end-of-season Brands International, when Gary broke the 250GP lap record on the Exactweld en route to fourth place, and equalled the 350GP record in another race. Looking good….

Not so good to begin with, as it turned out, though, when Noel failed to qualify for next season’s opening Euro-round at Vallelunga in March 1984. “There was a massive entry for the race, and they split us into two halves, odds and evens – and when it rained in practice, the Italians were all in the dry group and the rest of us in the wet!” he told me the following month, when we met up at Brands Hatch for me to ride his bike. By then he’d finished ninth in the second round at Jarama, outside Madrid – after which the Exactweld principals had a taste of the interest, and admiration, their bike aroused abroad. "We've got a much bigger following abroad than we do in Britain," explained Guy Pearson as we looked at his bike glinting in the spring sunshine at the Kent circuit. "After the Spanish race we could hardly get in the van for all the people who wanted to look more closely at the bike. Everywhere we go in Europe people are asking questions about it – they seem quite surprised when they find the chassis was built by us at home in England. Back here in the UK, though, it's just another Yamaha."

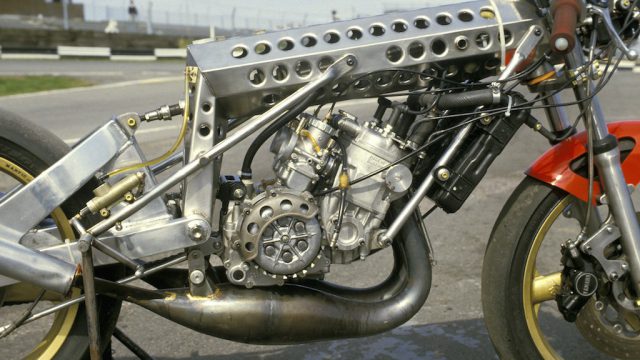

Pity, but prophets always did have a rough time of it in their own country, even though those 67 race wins gained in 1983 by Gary Noel on the Exactweld might be thought to represent some indication of how successful the bike's concept was. The chassis was a latter-day development of the spine frame principle employed by several different manufacturers down the years from Aermacchi to Zündapp, including the Rotax-powered Waddon 250GP bike of the early ‘80s, and especially the series of Egli specials. But Exactweld took up where Fritz Egli left off, constructing the spine from perforated stainless steel, a medium unconsidered by other chassis designers. "Everyone says stainless falls to bits," said Guy Pearson, "but our first 350s did over 5,000 racing miles without a single chassis fracture. Before we started Exactweld in 1977, we’d both worked for a time in an aircraft factory, as well as making Formula 1 monocoque chassis for Team Surtees, so we’d got a pretty good idea of the stress factors of most metals. The reason we had no trouble with stainless was that we never open-ended it. Everything was turned in to increase rigidity, plus it's the grade you choose and the way you work it that counts. We used the highest grade you could get, and TIG-welded it.”

Seeing Gary Noel's Exactweld TZ250 stripped of its distinctive streamlining for the first time in the Brands Hatch paddock before the chance to ride this remarkable creation, I was struck by the superb execution of every part of the bike. No amateurish abortion of the special-builder's art, it bristled with technical ingenuity and outstanding workmanship, which explained the two partners' insistence that they weren't interested in producing replicas for sale, since they almost certainly couldn't have done so at an affordable price. Part of the reason was the extensive use of titanium, for not only were all the fasteners, clutch nuts, engine case and gearbox studs and even the carburettor screws in the twin 38mm Lectron carbs made from this, but the springs in the standard Yamaha front forks were replaced by Exactweld-made titanium ones. Similarly, they reckoned the Öhlins motocross rear shock, fitted in an act of prescience at a time before the small Swedish firm had come to dominate road racing, weighed too much, so Exactweld copied the body in titanium and made a titanium spring, before refitting the original internals.

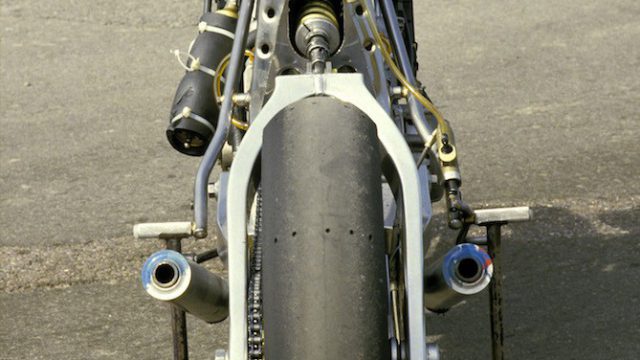

The hollow stainless steel spine weighed less than 4kg, even including the tubes for the front engine mounts and the footrests. The Monocross-style rear suspension employed a swingarm fabricated from Avional aircraft-grade aluminium, with the long Öhlins shock accommodated inside the hollow chassis spine. 18-inch Marvic magalloy wheels with hollow spokes were fitted, but even they weren't light enough for Pearson and Baldwin. "We'd use wire wheels if we could get titanium spokes made," Guy told me. Instead, later that season the Exactweld duo made their own magnesium and sheet alloy composite wheels, which together with replicating the fibreglass bodywork in what was then a new DuPont synthetic material nobody had heard of outside the body armour business, called Kevlar, meant that by mid-season the Exactweld had become the first 250GP bike to have to carry ballast to meet the 90kg class weight limit – a remarkable feat, considering that a stock ’83 Yamaha TZ250K (without the powervalve mechanism on the later ‘84 L-model) scaled in at 103kg with the same engine.

You noticed the light weight the first moment you accelerated out on to the track. Though the standard K-model Yamaha engine (Noel was later to adopt an L-model motor during this championship season) had been heavily modified by the team, the alterations had centred around improving torque and widening the power band, rather than simply increasing power. But, allied to the light weight and specially-designed streamlined bodywork incorporating a one-piece seat and tank unit (with the fuel compartment filled with Explosafe), these mods resulted in a bike that not only accelerated noticeably more smartly than a standard TZ250, but also had a phenomenal turn of top speed. On what back then was the world’s fastest road race circuit, the Exactweld had broken the 250kph/155 mph barrier at Chimay the year before, an amazing speed for a customer Yamaha motor without the factory racekit, and it was no coincidence that Gary Noel's first European title victory with the bike came in Austria the week after my test at the Salzburgring, then one of the fastest GP circuits in the world. Having been involved in a furious slipstreaming dice with six other bikes for most of the race, he was able to use the Exactweld's assets to best advantage by pulling out a vital 50-metre cushion exiting the chicane on the last lap. From there. Gary went on to score two more victories that year en route to the European title, at Karlskoga in Sweden and on home ground at Donington, finished second to local hero Stephane Mertens at Zolder, and sixth at Le Mans – one place ahead of future 500GP rider Niall Mackenzie on the carbon-framed Armstrong, which only attained a similar low weight to the Exactweld via that costly material, and had yet to win a major race, in spite of the greater financial resources behind it.

Riding the Exactweld at Brands Hatch the week before Gary’s Austrian debut victory, I had a dress rehearsal of how it would happen. Coming out of Clearways cranked hard over on the off-camber surface, I could feel the bike jump forward like a 500 as I wound open the throttle – yet the improvement in the power-to-weight ratio had been achieved without affecting the stiffness-to-weight proportion. The Exactweld hooked up the rear Dunlop without a trace of a squirm in the one corner on any track that back then was guaranteed to catch out a flimsily-fabricated frame, and with what nowadays seems a conservative setup with a 26º head angle and 18-inch front tyre, the bike felt nicely balanced into corners as well. "If you've got a stiff chassis, you can bring the front wheel back," said Guy Pearson. "We actually started out at 28º, but the frame's so strong, it doesn't flex at all, so we could get a faster steering response by steepening the head angle." Did Exactweld ever try a 16-inch front wheel? "We did, but to be honest it was no real improvement. 16-inch fronts were really only developed to help the bad-handling 500s get round corners quicker. We get a better tyre footprint and more stability from using an 18-inch front, and building the chassis properly." However, with no tyre contract and every penny counting, it was a sign of the team’s cash-pressed status that for my Brands Hatch test – and much of their title-winning season – the Exactweld 250 wore a front Michelin and rear Dunlop pair of slicks!

But Exactweld’s experimentation didn't stop with its choice of chassis material, for both leading link forks and rising rate rocker arm rear suspension were scheduled for assessment later that year, before a little matter of winning the European title got in the way of further experimentation. The leading links would have stiffened up the front end, where like many of their contemporaries Pearson and Baldwin were less than enamoured with the tubular front fork, before another crossover suspension component from the offroad world resolved that problem, in the shape of upside-down forks. Perhaps that was one reason for the only question mark I had after riding the bike, which was the use up front of just a single 300mm stainless steel disc off an RG500 Suzuki, gripped by a Yamaha TZ caliper. This didn’t impress with its initial bite, and in spite of its light weight the Exactweld did feel underbraked, especially for the tight Druids hairpin – though stamping hard on the hefty but not heavy Exactweld-made ten-inch titanium rear disc, helped deliver the right amount of stopping power. Maybe pad choice could have been an issue, but at least the single front disc reduced unsprung weight, leading to improved compliance from those adequate rather than exceptional early-‘80s Yamaha TZ forks, as well as minimised gyroscopic effect on the steering, making that relatively conservative chassis geometry steer even sharper.

With Gary Noel only slightly shorter than me, the riding position felt comfortable, in spite of having been tailored to suit him F1-style, via a plastic bag of expandable foam before the seat/tank unit was constructed. The bodywork was the only component on the bike that Exactweld didn't make themselves, though they did fabricate all the patterns. The exhausts were made by John Baldwin to his own formula, which cut out trial and error. In an uncanny preview 30 years ago of how exhaust gurus Akrapovic make such exhaust systems today, the pipes were laser cut on patterns, welded up, then hydraulically formed to produce a smooth expansion chamber for optimum flow. Riding the Exactweld TZ250 showed how effective the partners’ design was, as well as their own engine modifications to the stock Yamaha motor. This pulled from as low down as 7,500 rpm, with a good hit of real power from 8,000 rpm up to normal peak revs for a TZ250 in those days of 12,000 rpm. But when I stopped to adjust the suspension after a dozen laps of observing this redline, I was told I could let it run up to 13,000 if I wanted – some way beyond Yamaha's recommendations. Getting the best out of the Exactweld became much easier if you did this, and after only a handful of laps I was lapping in the 54 sec. bracket, less that 2 sec. off the lap record, which surprised both the team, and me – I was rather tall to get a lot of speed out of a 250, and it was a tribute to the bike's performance that the times came down as fast as they did. Coupled with the really excellent handling and the comfy riding position that made the Exactweld an untiring bike to ride hard, it’d have been an ideal machine for the longer 50-mile/80 km. European races, compared to the British short circuit sprints it was originally conceived for.

Or, even better, for full-length Grand Prix racing – which is where the Exactweld team headed for in 1985, after their European championship victory earned them guaranteed 250GP starts the following season. Only one thing wrong: incredibly, the team couldn’t gather sufficient sponsorship to do the job properly, so although the Transit van got replaced by a secondhand transporter, their GP effort was still a privately funded affair run on the back of the Exactweld business, which meant the partners had to take it in turns to accompany Noel to races, since the other one had to be back home earning the cash to fund this! Under those circumstances, although they inevitably found the competition stiffer in the Year of Freddie Spencer, Exactweld weren’t disgraced – as underlined by the names Noel out-qualified in earning a start for the first round at Kyalami in South Africa Angel Nieto, Guy Bertin, a certain Davide Tardozzi and – deliciously – Philippe Pagano all DNQ’d and failed to start the race. Dominique Sarron was added to the list for the next round at Jarama, but after two mechanical DNFs even better was in store at Hockenheim in Round 3, with Gary finishing 16th out of the 42-man field, ahead of both Pernods and Jacques Cornu’s Parisienne. But at the next round at Mugello, in spite of qualifying 23rd out of the 38 starters, this time he failed to take the start – the team had run out of spares to repair a seized motor, and the money to buy them. End of dream. “It was costing us a fortune in engine bits to keep the bike running, let alone in tip-top condition,” said Guy Pearson, “and at that level, there’s no other way to go racing. Making our own stuff was one thing – time and materials come cheap. But we didn’t have the money to keep buying Yamaha parts, so that’s why we pulled out and thought seriously about building our own Exactweld engine….”