Exclusive track test at Paul Ricard exactly 25 years ago of Honda’s unique oval-piston 750cc streetbike, of which just 322 examples were ever built for customer sale

I was one of the fortunate few to be invited to ride the NR750 that October day in the south of France, granted a total of 15 laps of the Paul Ricard GP circuit, complete with the 1.8km long Mistral Straight to unleash the Honda’s horsepower on

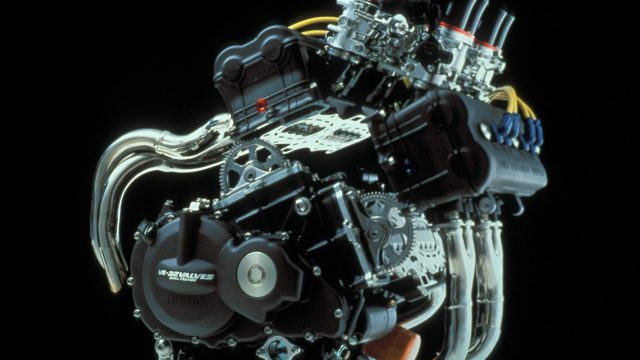

Exactly 25 years ago, the most exotic and most expensive series production motorcycle yet produced by any Japanese manufacturer was launched in the marketplace as a 1992 model, embracing a level of technology which even today seems extreme – even compared to today’s frankly more commonplace RC213V-S MotoGP racer-with-lights. For the Honda NR750, aka RC40, was the first and so far, the only opportunity for even a few wealthy customers to experience the fruits of Honda’s high-profile focus – obsession, even – on pursuing the holy grail of oval-piston engineering. It was a pursuit which began as a rule-bending exercise , but which by the October day in 1991 when 16 select journalists were invited to sample the results in a Paul Ricard press test, had been determined to offer significant mechanical advantages, beyond the initial objective of satisfying Soichiro Honda-san’s distaste for two-strokes, by developing a four-stroke to go racing with in the 500GP class. Honda by then held over 200 worldwide patents on individual aspects of the NR750’s engine design alone.

That being the case, it’s strange that as an engineering-led company, Honda has so far failed to follow up on the NR750 by using this patented technology elsewhere in its product range – especially after Takeo Fukui, the NR oval-piston project leader who was in due course promoted to head up HRC, later went on to become overall President of the Honda Motor Company. As such, it’s quite surprising he didn’t insist on introducing any of the bikes whose existence was hinted at by Honda insiders at the time, including a 250cc eight-valve single, and 600cc 16-valve V-twin, each also sporting EFI. So although at a price of ¥5,000,000 – back then the equivalent of $100,000 today – the NR750 was only ever intended as a luxury purchase, it now seems also to be a technical dead end, a case of Honda flaunting its engineers’ cleverness in producing such a bike, not the advent of a new era in four-stroke engineering.

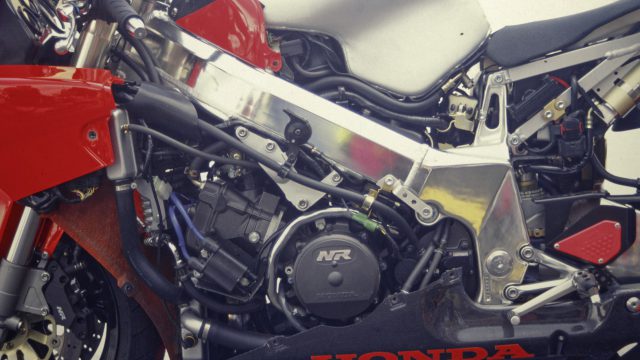

Yet, if you can ignore for a moment its ground-breaking engine format, the NR750 was an important step forward in two-wheeled performance, as the first Japanese sportbike to be fitted with fully mapped multipoint EFI, and the first from any country to feature upside-down forks, carbon-fibre bodywork, titanium anything, side-mounted radiators (later copied on Honda’s V-twin Firestorm), and exhausts under the seat. And in terms of styling, 25 years on the NR750 streetbike is still by any standards the most breathtakingly gorgeous, gloriously sexy, downright voluptuous, and irresistibly seductive piece of Oriental two-wheeled splendour yet seen, one which back then took motorcycle design in a new direction stylistically as well as mechanically. The work of Honda’s design team headed by Mitsuyoshi Kohama, later responsible for the first CBR900RR Fireblade and the RC211V MotoGP racer (and its abortive street replica), this not only rivalled the best that Italy had ever produced, but even inspired the Michelangelo of the motorcycle, Massimo Tamburini, to copy it – as he himself later freely admitted.

Yet a total of just 322 examples of the NR750 were ever made, with 220 built in 1992 – of which 20 were the 100bhp RC41 variant for the French and Japanese markets – plus 102 more bikes in 1993, before production was terminated as the orders dried up for the most expensive street bike ever to reach series production – if that’s what you call making one bike a day for the single calendar year it was on sale for from October 21, 1991, each built to specific order accompanied by a 25% deposit, on a first come, first served basis.

I was one of the fortunate few to be invited to ride the NR750 that October day in the south of France, granted a total of 15 laps of the Paul Ricard GP circuit, complete with the 1.8km long Mistral Straight to unleash the Honda’s horsepower on – well, such as it was, for I remember being slightly underwhelmed by the occasion, especially after having been allowed to ride the NR750 endurance racer at the same circuit five years earlier. That was a truly mind-blowing experience, and having the NR racer’s then-considerable 160bhp delivered in such a usable, accessible way, made you realise Honda had made a real breakthrough in overall engine performance, and especially its management. It wasn’t just the sheer fact of conceiving an oval-piston motor and making it work at all in the first place that you had to admire, even if the engineering challenges were mind-boggling. It was how much engine performance was unleashed by the oval-piston design, how it was delivered, and how the power was put to the ground in those days before electronic rider aids and even fuel injection were commonplace, that was so truly impressive.

But you certainly didn’t obtain the same thrill from riding the street version of that motorcycle – apart from just one thing: the fact that the engine would spin silently and smoothly up to the 15,000 rpm revlimiter without a hiccup, and especially without tangling valves or bending conrods. But if you rode the NR without looking at the large white-faced son-of-Veglia rev-counter positioned in the centre of the busy dash, you could have been forgiven for thinking that the NR750 was merely a more luxurious, slightly strangled, more sanitised update of a round-piston RC30. Since, like the RC30, the NR was a 90º V4 with 360° crank throws, it had the same deceptively flat exhaust note, heavily muffled by the weighty 8-4-2-1-2 stainless steel exhaust exiting beneath the seat. Like the conventional V4, it had a mile-wide power band and ultra-flat torque curve, peaking at 11,500 rpm with 7.0kgm/68.65Nm on tap. But here was the crunch: Honda had chosen to restrict the NR’s output to ‘just’ 125 bhp at 14,000 rpm on paper, and not only that, but this über-Superbike with all its technological wizardry scaled a hefty 222.5kg dry – or well over 250kg fuelled up, and ready to roll.

OK, riding the NR proved it was no over-priced, over-weight, under-powered damp squib, for as Honda management was then at great pains to underline, it wasn’t intended to be a hard-nosed race replica, but a more well-rounded performance motorcycle offering a superior combination of speed and comfort. According to engine designer Suguru Kanazawa, Honda engineers could have obtained over 140 bhp in street from the 32-valve 750cc engine if they’d wanted to, although emissions and noise regulations would have made it difficult to get more. But they deliberately opted for a reduced output in favour of increased rideability, and likewise highlighted rider comfort and control rather than emphasising race-level handling and light weight through advanced (and costly) materials. It just wasn’t the kind of bike everyone was expecting, and maybe that was one reason its sales were so disappointing – Honda had spoken of being ready to make three bikes a day for one year, with a 1,000-unit ceiling, but ended up manufacturing just one third of that number.

So when after more than a decade of hope and anticipation, an admirer like myself of Honda’s courage and determination in pursuit of the oval-piston concept finally climbed aboard the NR and thumbed the start button, the initial reaction was frankly one of disappointment. Because you knew it was all so technically different beneath that fire-red skin, you expected it should feel immediately different to ride – and it wasn’t. Part of the blame lay with Honda’s marketing department – they’d done their job so well that any bike would have a hard job living up to the expectations generated by the hype. Another reason lay with the decision to restrict the power output, for the NR750’s acceleration was smart but not spectacular, not aided by the fact that the bike was apparently way overgeared. Honda claimed a top speed of 263km/h in Japanese testing, but at the end of Paul Ricard’s 1.82km-long Mistral straight, the longest stretch of tarmac on any racetrack in the world back then, I’d barely see 250km/h on the ultra-legible LCD digital speedo tucked behind the base of the titanium-sprayed screen. Having decided to give away some performance by sacrificing engine power, Honda engineers might equally have gained some acceleration at the expense of top speed if they’d wanted to – but they didn’t.

But maybe some explanation for that was the very thing Honda was so proud of – the NR750’s seamless power delivery throughout the rev range. The closest thing I can equate that to is riding a Norton Rotary racer of the same era. Like the Wankel-engined bike, the NR made power practically from off the clock, with no less than 4.5kgm/44Nm available at a mere 3,000 rpm, and 5.6kgm/55Nm at 7,000 revs. This ultra-linear, ultra-smooth, progressive delivery was also ultra-deceptive, even though Honda’s engineers had actually designed in a couple of blips in the power curve, simply to emphasise its progression. The reduced friction of the oval-piston design, coupled with the short engine stroke and surprisingly high 11.7:1 compression, meant engine revs picked up fast, but always in linear mode. Even as the tacho needle neared the 15,000 rpm redline, there was no sign of strain or effort, just liquid revs, silently and effortlessly delivered. Then it was time to shift up, which was when you discovered the gearbox ratios were quite wide but very evenly spaced, averaging slightly less than 2,500 rpm between them – not a typical sportbike’s close-ratio cluster. Shift action was impeccable, with the slipper clutch whose large diameter surely restored a good bit of the torque handed away via the short stroke format and minimal crankshaft mass, also smooth in action and take-up. And, as on the RC30, this still had lots of engine braking left dialled in, which you could use without chattering the rear wheel, resulting in the temptation to ride the NR750 like a two-stroke, braking hard into a turn and zapping down gears two and three at a time as you did so, just like a modern Superbike!

Yet if truth be told, the race track was not the NR750’s natural habitat, and at Paul Ricard the reduced ground clearance caused by the protective bodywork’s deceptively ample girth rapidly became apparent. The hero tabs on the flip-up footrests might have been longer than usual to discourage us from ruining the high-tech, big bucks paint job, and the carbon fibre-reinforced plastic fairing, but it was ridiculously easy to ground them on either side through a chicane, even without hanging off the bike unduly. The grip from the specially-developed Michelin radials was much too good for the ground clearance, although when you stripped the Oriental princess down to her underwear to ogle at what lay beneath, it was hard to see why. I had no such problems with the racing NR750 I rode on slick tyres at the same circuit five years earlier, and I couldn’t see how adapting it to the street made the bike any wider.

Still, the Honda’s Showa suspension was outstanding, especially over the awesome bump on the apex of the turn after the pits, which had caused so many crashes at that year’s French GP run at the same circuit. The NR’s meaty 45mm upside-down forks delivered outstanding compliance and lots of feedback, even when exposed to the massive braking potential of the 310mm floating front discs and their four-piston calipers over any of the car-inspired ripples littering the track surface. As I’ve subsequently found in real-world riding a Spanish friend’s customer NR750 occasionally on twisting mountain roads, the extra safety margin these brakes offered in real world terms was a genuine plus, but not to the point of overkill. In spite of the oval-piston Honda’s hefty weight, it felt more like a 165kg Superbike when braking hard at the end of the Pit Straight at Paul Ricard, slowing well but steering into the turn easily and precisely, without the suspension freezing. Then, let off the brakes just as you hit the rough patch of tarmac announcing that notorious bump, and let the Showas do their stuff. Magic. Crack the throttle hard open again, and the outstanding Pro-Link rear suspension glued the Michelin tyre to the road, while shoving all that lovely, liquid power through it. I’d never ridden a streetbike with better suspension than the NR up to then, and it’d take another decade before Öhlins brought the full benefits of their racetrack R&D to the street, before I would.

But an important factor in the NR’s unflustered behaviour under acceleration out of turns was the way the power was delivered, with a smooth but immediate pickup, allied with a light yet controllable throttle response. Until then, only riders of Ducati desmoquattro or YB4 Bimota streetlegal Superbikes had experienced this, and both for the same reason. Amazingly, the NR was the first Japanese 750 to be fitted with multipoint digital EFI, and compared with the jerky pickup of the flat-slide carbs by then commonplace elsewhere, you might as well have stacked Pavarotti up against the Karaoke singers in his local pub: they could all sing along, but only one did it properly. It was obvious that the NR750’s fuel injection was the one feature that would have most immediate and widespread application, rather than the oval pistons…..

Well though the NR braked and steered, there was no getting away from the fact that this was a big, heavy bike, and working it from side to side in a tight chicane like the famous Ricard Pif-Paf, or a faster sequence of turns like the last two turns before the pits, required a considerable amount of physical effort. The NR750 wasn’t a razor-sharp race replica like the RC30, and though it was a lot more relaxing and comfortable to ride than one up to a certain level, beyond that it was more sport tourer than Superbike. You sat in the oval-piston bike rather than atop it, as on the RC30 and its kin, with correspondingly less weight on your forearms and shoulders – this still has to be one of the best thought-out and most relaxing riding positions of any bike with even mildly sporting pretensions, with an ideal handlebar to seat to footrest relationship. Lucky owners.

Yes, lucky – because while the NR750 wasn’t the ne plus ultra performance bike everyone had expected the oval-piston concept to produce in the unlikely event it ever reached production, what it curiously was – if you could forget that astronomical price tag for a moment – was the ultimate real world motorcycle. It was very comfortable, handled superbly, braked as well as a Superbike, had lots of sensible touches like the digital speedo, and was extremely satisfying to ride, if a little heavy to swap direction with – perhaps a function of the wide 16-inch front tyre, with its very rounded profile. While currently unfashionable, this had the same rolling circumference as a 17-incher with a lower aspect ratio, only provided more comfort and a larger contact patch, without the gyroscopic instability problems of the old low-profile 16-inchers of the 1980s. The styling is sensational even 25 years on, and back then for that hefty price tag, you had the satisfaction of knowing that beneath the Honda’s high-class threads lay the cutting edge of four-stroke oval-piston fuel-injected engine technology. Maybe the NR750 wasn’t a bargain, exactly – but maybe not such a bad deal after all, especially with examples being advertised today for upwards of $200,000….!

* * * * *

Photo credit: Phil Masters